Here’s the thing:

we don’t really know what bass actually is

– although we certainly have instinctive understanding of its importance.

Super-producer and Killing Joke bassist Youth sums up a huge amount of the appeal and complexity thus: “You feel bass more than you hear it and you feel it most in gut and your groin. So it can activate your sexual response, but also can root us and earth us. Like when you’re flying at a rave, it’s the bassline that can be your lifeline and save you from a complete meltdown. For me as a bass player, it’s not just locking the rhythm down and becoming a moving tone for the kick drum (which is a big part of it): it can also provide counter melody, carry the melody and provide harmony. As a producer it’s the same, a great bass line will lock in the drums and make you want to move to the groove. It will seduce you into listening to the song.”

Anyone involved deeply with music – especially soundsystem music, of course – could tell you similar things. But actual research into exactly how these mechanisms work and why we feel these responses is all-but non-existent. Search medical research literature for anything to do with low-frequency sound and the sense is of an inconvenience, or even something dangerous: it’s essentially only mentioned in conjunction with health threats from vibrations to forklift drivers, pilots or other operators of heavy machinery. And look for scholarly discussion of it, and again there is very little, perhaps because it is seen as base or basic. While the articulation and detail of sound and speech very often take place in the high frequencies, bass seems to be all about impact and immediacy. It’s the musical foundation or framework on which other musical structures are built, something that is reinforced in our minds by the literal description of it as being “low”.

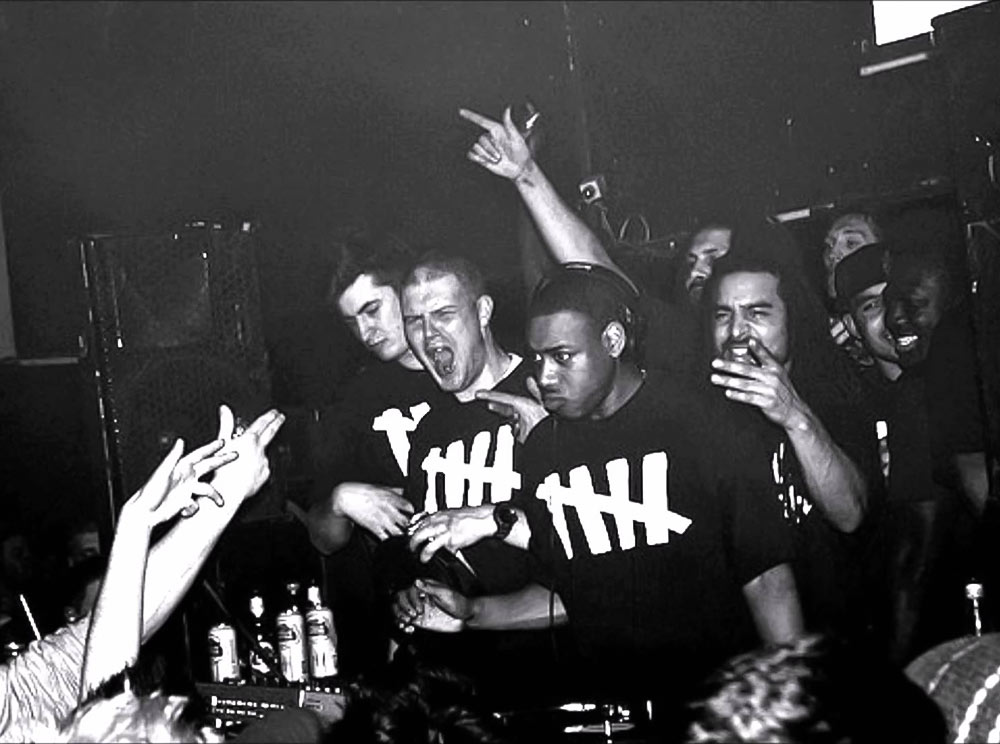

There’s a great weight of collective assumption that holds music with emphasis on the bass to be “low” culturally, too. Ask what people think of when they think of extreme bass and as likely as not they’ll come up with images of huge speaker stacks, the thudding of clubs and parties penetrating walls, trunk-rattling trap 808s and bashment syncopations, maybe the infernal grind of Black Sabbath or Sunn o))): all wonderful things, of course, but not considered by most as particularly cerebral experiences, and a long way from the harps and violins that your average punter might associate with high culture. And think of the pivotal basslines of dance culture – “Sex Machine”, “Sleng Teng”, those 808 kick patterns, “Acid Trax”, “Just Want Another Chance” (aka “Reese Bass”), “LFO” – these are melodically and rhythmically among the simplest motifs in all of culture.

As anyone who has immersed themselves in soundsystem culture knows, though, bass is not just a blunt weapon. The first time I went to DMZ, ten years ago now, Loefah said something that stuck with me: that there was a tension in experiencing bass at high enough volume, between the comfort of the womb and the fight-or-flight reflex that comes with the sense of something that could overwhelm you. That is to say, when you are surrounded by speakers bigger than you, by sounds bigger than you, that penetrate through you, you are embraced in a safe space, but filled with the will to action. As Youth puts it, “dubstep has changed the way we listen to bass. If you listen to a great dubstep tune on a loud Funktion-One, a whole new bass beast emerges, that literally stuns every atom of your body and rips through to the core of your bowels.” This duality of threat and comfort is also expressed by Alvin Lee Ryan of musique concrete-inspired electronic duo KAS-tro – also drummer for darkside bass manipulator Haxan Cloak: “I think people’s response to sub really varies depending how intrusive or appropriate it is. Sometimes I think it is a spectacle – like when you listen to thunder, or slam a door in an underground car park – but sometimes it is comforting: the familiar rumble of the tube train approaching makes me feel quite nostalgic when I have been away from the city for a while.”

That description of DMZ as womb-like isn’t that far-fetched, either. “It’s relatively uncontroversial,” says Sophie Scott, professor of neuroscience at University College London, “to say that, when when you’re born and you open your eyes for the first time that’s the first time you ever see faces and you’ve got a blank slate for the visual world. But you don’t for the auditory world, because you can hear in utero [in the womb]. And what you hear in utero is the low frequency stuff because everything else is filtered out. We know that babies learn from that because they pick up the melody and the rhythm of their mum’s voice. The interesting thing there is that because the high frequency stuff is filtered out, they’re not hearing speech as such. They’re hearing low-frequency melody and rhythm – they’re hearing and feeling it – and that gives them the basics of the language as a pattern, not as a conveyor of meaning.”

“We know babies learn from this,” she continues, “because babies come into the world knowing not only about their mother’s own voice but about the rhythm of the mother tongue from this. They will react to that language in a way they don’t to others. And I think this may speak to why we like music on such a basic level, because we’ve had experience of pitch and rhythm, particularly at low frequencies. You find in all cultures, parents will sing to babies to calm them. It’s one of the few universal things that will calm them, other than being held or fed – to the point where even deaf women who have never heard their own voices, if they have a hearing baby, they will sing to that baby. That’s how profound the baby’s need to hear this is, that they will manage to get it out of someone who literally doesn’t know what they’re doing.” It’s not a great leap to say that low-frequency, rhythmic sound – that which we hear in utero – literally forms our sense of what it is to think, to communicate, to be human.

But when we take it to the club, to the concert arena – or indeed when we plug in the SUBPAC – this sense memory is translated into something high-impact, elemental even: “if your chest ain’t rattlin’ it ain’t happenin’” as DJ Pinch famously put it. There is something profound about the totality of the experience of low-end music that has no equivalent or analogy in any other art, that can’t be faked or replicated in any other way. Subsonic vibration, for example, can be used to signal something happening in the real world. Tony Russell, the other half of KAS-tro, points out that “In a lot of ways sub is possibly the first sound we are tuned to listen for it’s usually the precursor to something happening like a train arriving or the noise before you enter a room in a club, and in films they use it to build tension to introduce the idea that something is going to happen. I think it’s quite primal.”

But it’s not just about vague rumblings: sub bass can be used with extraordinary precision, too. Increasingly over the past couple of decades, the ability to manipulate the dynamics of that experience open up an entirely new artistic and social canvas. Dubstep in particular saw a quantum shift in the sophistication and importance of bass tones, but it’s far from the only place this has been happening. From the precise tweaks and abstractions of gallery-oriented artists like Alva Noto and Ryoji Ikeda to the spiritually-inclined ideas behind “frequency baths” inspired by gongs and digeridoos that are increasingly gaining traction via the “wellness” industry, there is a whole range of subtlety within that dramatic impact that is being explored creatively around the world.

Yet powerful though these effects can seem, scientific and clinical research into them is still barely existent. But there are some strands of science that can tell us a little about the intense power of soundsystem sound. In part II of this feature, we’ll look a little at them….